The documents which give information about the 13th century Queen Puduhepa, wife of the Great King Hattusili III (1275-1250 BC) are prolific. Her fascinating personality and strength of character are attested in numerous letters, prayers, sacrificial and ritual texts from Bogazkoy and Ugarit. There also exist a number of official documents concerning the duties of Hattusili III where Puduhepa’s name appears alongside that of her husband. Among the historical texts referring to his reign is the autobiographical Apology of Hattusili III, in which he justifies his deposing of his nephew Urhi-Tesup, and which opens with the words of the great King Hattusili and the Great Queen Puduhepa.

On his return from the campaign against Egypt, where he had assisted his brother Muvatalli at the Battle of Kadesh in 1275/4 BC. Hattusili arrives at the city of Lavazantiya in Kumanni with the purpose of making the customary sacrifices to his protective goddess Ishtar. There, on the instructions of the goddess, he marries Puduhepa, the daughter of Pentipsarri, priest of Ishtar. The goddess bestows on them the love of a husband and wife, and they have sons and daughters. Another version of Hattusili’s autobiography contains more detailed and interesting information concerning this marriage. Here, not only is Puduhepa the daughter of a priest, but she is also referred to as a handmaiden of Ishtar in the city of Lavazantiya, i.e. a priestess. It is also stated that Hattusili did not take Puduhepa as a result of his own desire, but married her at the command of Ishtar, who appeared to him in a dream. So Hattusili, before he was king, and probably not very young, married a noble girl from a family of high priests in Kumanni. The family of only two Hittite queens is known for certain. One of these is Tavananna (III), the third wife of Suppiluliuma l, who was the daughter of a Babylonian king. The second is Puduhepa. In the introduction of a votive dedication to the goddess Lelvani, composed sometime after she had become queen, probably during her most powerful period. Puduhepa refers to herself as Puduhepa, the daughter of the city of Kumanni. Puduhepa, like almost all of the queens of the Hittite Empire, bore a typical Hurrian name, in accordance with the land of her birth.

The names of some of the children of Hattusili and Puduhepa are known. Their eldest son was Tuthaliya lV, who succeeded to the throne on his father’s death. Another son was Nerikkaili, who married the daughter of Bentesina, king of Amurru. One daughter, Gassulaviya, was married off to Bentesina on condition that she became queen.

Besides the children of Hattusili by Puduhepa, documents also refer to the existence in the palace of other children of the king. In a letter, Puduhepa writes: … “The daughters of the king whom I discovered when I came to the palace gave birth with my assistance, and I raised their children. I also raised the children who had already been born and I made them commanders in the army.” Hattusili’s son Nerikkaili and his daughter Gassulaviya, who became son-in-law and wife of the neighboring king of Amuru, appear not to have been the children of Puduhepa and must have been born to a previous wife of Hattusili. Written sources attest that Puduhepa was the mother both of the daughters sent as brides to Ramses II of Egypt, and of Hattusili’s successor Tuthaliya IV. Egyptian sources refer to one of these daughters by the Egyptian name of Mahornefrure or Manefrure. According to Egyptian temple inscriptions, Ramses married this princess in the thirty-forth year of his reign, and she became a member of his harem. Correspondence between the Hittite and Egyptian rulers discuss at great length this marriage arrangement and dowry of the princess, from which it can be seen that Puduhepa was personally involved in arranging royal marriages for her children.

The reign of the Great Queen Puduhepa is so well documented that it is clear that she played a very active and successful role in affairs of state, in political, legal and religious matters alike, performing her duties alongside and on an equal footing with her husband, as well as independently. It is unfortunate that the version of the famous Treaty of Kadesh written on a silver tablet has not survived. On one face of this tablet was the stamp of the Great King Hattusili III, and on the other face was the stamp of the Great Queen Puduhepa.

The letters concerning the political marriages, or plans for marriage, between the Hittite and Egyptian dynasties, are particularly important in revealing the independent part played by Puduhepa in diplomatic affairs. As many as 15 letters were received by Puduhepa. Those sent by Ramses ll are identical to those he sent to Hattusili, showing that the Egyptian king himself accorded an equal status to the queen and the Great King. Possibly this was one of the rules of politics dictated by the state laws of the period. The style of the letters from Ramses II is very striking. The tone is quite formal, and importance is given to the use of long and polite formulae. In one of his letters, Ramses addresses Puduhepa as my sister and mentions the comfortable state of the land of Egypt and his own good health. Then he expresses his wish to the queen that she should also possess the same favorable circumstances as he himself does.

Among the letters received by Puduhepa are diplomatic letters from Egyptian queens, which seem insignificant in comparison with her other correspondence. Only one letter is known from Ramses II’s wife Naptera/Nobretari, and another from his mother Tuya. In this light, the letter sent by the Egyptian pharaoh Tutenkamen’s young widow to Suppiluliuma I, requesting one of his sons as a husband, is unique.

Puduhepa also sent a letter personally to Ramses II, concerning the plans to marry her daughter to the king of Egypt. These documents manifest the significant and active involvement of Puduhepa in foreign policy and in the arrangements for diplomatic marriages with the aim of creating international peace. This is a situation which does not apply to all Hittite queens, although it seems that a queen was required to possess the personality and strength of character to be able to wield independently her official authority. The official status of a queen according to the Hittite constitution, however, is not completely certain. Equality between a king and queen in international politics is indicated by the royal correspondence, and the use of personal seals of queens to ratify agreements indicates that queens made the decision in their own names. No other queen, however, illustrates these conditions as well as Puduhepa.

There are no documents which explain the social activities Puduhepa performed alongside her political duties and functions. With the Hittites, however, as with the whole of the Near Eastern world, the royal social functions were closely related to religion and cults, and some ritual texts show that Puduhepa was in charge of the activities associated with the cults. This subject will be touched on below in a discussion of the Queen’s involvement in the sphere of religion.

Among the documents which demonstrate the active independent role played by Puduhepa in judicial affairs, there is a group of texts, referred to in judicial affairs, there is a group of texts, referred to in Hittite literature as the Ukkura Affair, which records the minutes of court proceedings.

One interesting document of this type, more specifically appertaining to the international shipping laws of the time, was discovered during excavations of the ancient city of Ugarit. The text, written in Akkadian, concerns the case of a Ugarit ship which had sunk outside the limits of its own waters. On the front face is the seal impression of Puduhepa. It is understood that the decision of the inquiry was made in the name of the Hittite king, most probably Tuthaliya IV when he was too young to assume control of his responsibilities and the reins of power were in the hands of his mother Puduhepa.

The same situation occurred if a king was absent because of religious duties (cult tours etc.) or on the campaign when legal documents were endorsed by the queen’s seal. The tablet under discussion is Hittite, and the sailor mentioned in the document is a subject of the Great Hittite Kingdom. The minutes of the inquiry are written in epistolary style.

“My sun writes thus to Ammistamru: When the man from Ugarit and Sukku came to trial in the presence of My Sun. Sukku spoke in this way: ’His ship broke up against the quay’, but the man from Ugarit said: “No, Sukku forcefully broke my ship on purpose”. My Majesty gave the following verdict: “Let the head of the Ugarit sailors swear on oath; then Sukku will pay for the ship and the goods on it.”

This verdict of compensation was issued in the name of the justice of the Hittite king and stamped by Puduhepa on behalf of her son. The person liable for reparation, who had been found guilty of causing the damage to the ship, was Sukku, a citizen of the Hittite Kingdom. The name of the person awarded damages is not mentioned; he is referred to only as the head of the Ugarit sailors and was probably a ship-owner or merchant of the city of Ugarit.

A number of interesting documents show that the great and powerful Queen Puduhepa also had political influence on the small kingdoms which were subject to the Hittite state. The peace between Egypt and the Hittites also improved the relationship between Egypt and the small vassal states of the Hittite Kingdom. During the reign of Ramses II King Niqmadu II of Ugarit, a city dependent on Hatti made a peace treaty with Egypt at the request of Puduhepa.

Joint seal impressions of Puduhepa and Hattusili III have been found at the Hittite capital of Hattusa (Bogazkoy) and at Ugarit (Ras Samra in northern Syria). At first glance, it can be seen that these are stylistically different from those of other kings, the writing, and motifs characterized by plasticity. At the top of the circular seal is a winged sun disc. The disc-shaped like a petalled rosette and standing unattached from the wing on either side. The plastic form is seen especially with the signs which represent the queen, the volute symbolizing Great and the female head symbolizing Queen. The head symbol is worked realistically in the manner of a relief statue, and the smallest details are picked out on the disc-shaped head-dress and fine veil which hangs to the neck.

Four independent seal impressions belonging to Puduhepa have been discovered, one at Tarsus, one at Ugarit and two at Bogazkoy. The plastic style is even more evident with these than with the joint seals. The composition of the motifs and signs is symmetrical and decorative, and these had been carved deeply into the surface of the seal, emphasizing the plasticity of the relief impression on the bullae. The name and title of the queen are given in pictographic signs (Hieroglyphic Hittite) in the field at the center of the seal, and this is ringed by a cuneiform legend, although the legends of two of Puduhepa’s seal impressions are damaged. In the field, at both left and right, appears a small female head with a disc-shaped head-dress, symbolizing Queen, on top of which is the volute which symbolizes Great. Thus, the title SAL.LUGAL.GAL (great Queen) is written on both sides. In the upper part of the field is the winged sun disc. The sign for the title My Sun (My Majesty), symbolizing royalty. Down the center of the field, below the sun disc and between the two female heads, are the four signs of the queen’s name: Pu-tu-he-pa. The cuneiform legend around a royal seal generally gives the name, titles, and ancestry of the rulers.

Among the finds from excavations at Bogazkoy and Ras Samra are clay tablets and bullae which bear the joint seal impressions of Puduhepa and Hattusili III. Also from Ugarit (Ras Samra) is a seal impression of Puduhepa’s son Tuthaliya IV which displays an unusual composition and plastic style. In the cuneiform legend around the field, the king is the styled son of Hattusili and Puduhepa, indicating that Tuthaliya was not content with giving merely the name of his father, but also wanted to record the name of his mother. This is the only known example of a royal seal which specifies the name of the king’s mother. No joint seals have been discovered as yet of Tuthalia IV with another queen.

Besides these examples of seal impressions on clay bullae or tablets, the personal seal of Puduhepa on one face of the silver plaque which originally recorded the Treaty of Kadesh is also known, from Egyptian sources.

All of these documents, in particular, the independent seals which bear the queen’s name, provide the clearest proof of the equal status of the Hittite queens with the kings and the independent position of the queen. Despite the fact that Puduhepa bears the official titles of the rule, it is notable that she is not represented by the title Tavananna. Nor is her husband Hattusili referred to as Tabarna on either written documents or on seals.

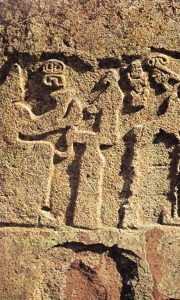

The publication of ritual texts has enabled us to appreciate the Hittite queen’s role in important religious activities and sacred rites. The queen took her place as the chief priestess, alongside the king who was chief priest of the Hatti lands. The documents in which the religious duties of the Hittite queens are mentioned are known collectively as Descriptions of Festivals. They show that the queen was responsible for conducting numerous religious ceremonies, either together with her husband or independently. When it is recalled that there was a female deity at the head of the Hittite pantheon, the Sun Goddess of the city of Arinna (the Hurrian Hepatu), the involvement of the Hittite queens in the ceremonies is recorded not only written texts but also on rock reliefs. One of the most important of these is that Fraktin in Cappadocia: other examples are those of Alacahöyük and Aslantepe (Malatya). It is known from the descriptions of the rituals that the king and queen wore special garments during the ceremonies (H. anniyat-/KIN-att). They are also shown dressed in these special ceremonial costumes on the rock reliefs. On the Fraktin rock relief, Puduhepa is depicted clothed from head to foot in her priestess’ robes, pouring a libation to the goddess Hepatu. This relief is the only certain archaeological evidence of a scene showing Puduhepa pouring a libation to Hepatu.

The name of Ishtar, goddess of the city of Lavazantiya and protecting deity of Puduhepa, occurs frequently in documents of Hattusili III. The signs which denote the Hittite Goddess Ishtar distinguish her from the Mesopotamian Ishtar (goddess of love). The Hurrian name of this goddess was Sausga, and she was brought by the Hurrians to Anatolia and integrated into Hittite culture with the local deities. The Ishtar of Lavazantiya was not a goddess of love, but in fact had warrior characteristics, which suited the serious temperament of Puduhepa. The protecting deity of Hattusili was Ishtar of the city of Samuha, who had the same male characteristics and attributes of a warrior-god.

After Hattusili III had deposed his nephew Urhi-Tesup and appointed himself king, the royal couple had prayers composed which open with an invocation to the Sun Goddess of Arinna, the chief goddess of the pantheon, and go on to thank her for her favor. The prayer begins as follows:

O Sun Goddess of the city of Arinna,

my lady, mistress of our lands.

Queen of Heaven and earth,

mistress of the kings and queens of the land of Hatti.

This Proto-Hittite, native Anatolian principal deity of the Hattians entered the official pantheon together with her family. Written sources and rock monuments (in particular the open-air sanctuary at Yazılıkaya) of the 13th century BC show that the Hurrian gods had become members of the Hittite pantheon and taken the most important positions, probably as a result of the influence of Puduhepa. The principal Hurrian goddess Hepatu was identified with the Sun Goddess of Arinna. Hepatu was the protecting deity of the Hittite state and its armies, at the same time possessing the characteristics of a mother-goddess. The Hittite expression a thousand gods of the land of Hatti illustrates the magnitude of the Hittite pantheon. Within this sizeable realm of deities, the goddesses held special importance. Each deity, from the chief pair to the gods of springs and mountains, was the focus of a cult, with the result that the official and royal calendar was pretty much taken up with duties related to these cults. In the lavish ceremonies of the state cult, the queen took her place as chief priestess beside her husband.

It is notable that protecting goddesses of both Hattusili III and Puduhepa had the characteristics of a battle goddess. The goddess to whom Puduhepa promises offerings when she is requesting that her beloved husband (the life of my Sun) be protected from ill health, however, is Lalvani, who was a infernal goddess, associated with the underworld (there is no definite evidence to support E. Laroche’s theory that Lelvani was identified with Ishtar of Samuha).

But what is known about Puduhepa as a woman, and of her feelings? Unfortunately, no personal documents belonging to Hittite women are known, and so nothing is known about the private life of Puduhepa. A little light is thrown on the question of her feelings in the texts which mention the vows made to Lelvani by the Great Queen Puduhepa, daughter of the city of Kumanni and the dreams of the queen.

There is no doubt whatsoever that Puduhepa was a loyal wife to her husband, and regarded him with devotion and respect. The king himself writes about his childhood when he suffered from bad health and the worries of being close to death. After pledging himself to Ishtar of –amuha whilst he was still young, his health recovered and he developed into a strong young man. Despite this, however, it appears that his ill health must have returned when he became older. The prayers made and the offerings promised to the gods for the continued good health of the Sun (king) and a long life reflect the deep love and devotion of Puduhepa towards her husband and her fear of losing him at any moment. The most well-known and well-studied of this kind of document comprises the vows made to Lelvani, infernal goddess of the Underworld. In these documents, Puduhepa promises various kinds of offerings in return for a long life full of good health for the king. The kind of offerings promised to include gold and silver goblets, vessels and drinking horns, gold images of the god, statues or busts of the king, and sometimes living things such as herds of animals, and NAM.RAS (civil prisoners/deportees) as cult personnel.

One of the most interesting aspects of Queen Puduhepa’s votive texts is that the family members in the service of the cult of the goddess Lelvani are mentioned individually by name. Thus, it is possible to distinguish two groups among the temple personnel-young girls and boys, and widows with children referred to as ut/dati. Puduhepa involved herself in the family lives of these people, arranging marriages for the young girls and assigning the upbringing of the orphan children to the supervision of relatives.

The women referred to as SAL udati, who served the temple of the goddess along with their children, are given an important place in the text. The duties of these women comprised the production of dairy products. The temple personnel also included males who are referred to as NAM.RA. These men worked for the temple economy, performing various tasks such as planting fruit trees and working in a capacity as bakers and dairymen. The personnel was recruited annually, to replace those who had died, and a census record was kept. These procedures can be traced in the texts over a period of five years.

All procedures connected with the temple of Lelvani were related to the purpose of helping to provide the king with a healthy and long life and were very probably performed in the city of Kumanni. Puduhepa’s organizing of the temple personnel, the recruiting when necessary, the duties performed, and the arrangements for the annual sacrifices are all recorded. These texts, then, of which there exist a number of versions, are not only of a religious nature, but they are also administrative documents which give information about the socio-economic organization connected to the cult, and they reveal the economic importance of the temple in the 13th century BC.

It is also known that Puduhepa had a series of religious documents rewritten, as well issuing orders that scattered texts be collected and organized. These were the texts related to the ceremonies of the hişuvaş or işuvaş festival. The tablets record that the queen reorganized the ceremonies and the cult.

Despite the abundance of documentary evidence for this period, however, it is known when or how either King Hattusili III or Queen Puduhepa died. Nor has the tomb of the couple yet been discovered among the wealth of architectural structures at Hattusa.

Letters & Other Documents from The Great Queen Puduhepa:

Prayer of Queen Puduhepa to the Sun Goddess or Arinna

Bogazkoy (Hattusa)

Hittite Empire, 13th century BC.

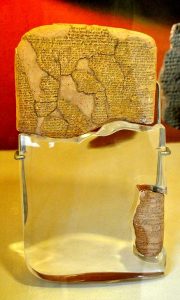

Language: Hittite (cuneiform)

Baked clay. h:21.7 cm. w:17.7cm. th:6 cm.

Istanbul Archaeology Museum Bo.2125 + 2370+8159

Upper edge and corners intact. Tablet restored from many pieces, but still with fragments missing and deep cracks. In Hittite texts, Queen Puduhepa is always portrayed as a dependable wife, in war and peace, in sickness and health, to her husband. King Hattusili III. It is known from documentary sources that the king had a weak constitution, and the queen lived in fear of losing him at any time, so she frequently made prayers to the gods for her beloved husband to have a long and healthy life, and made valuable offerings to them. Here, Queen Puduhepa beseeches the Sun Goddess of Arinna:

…To the Sun Goddess of Arinna, my lady, the mistress of the Hatti lands, the queen of earth and heaven. O Sun Goddess of Arinna: but in the land which you made the Cedar land you bear the name Hepat. I, Puduhepa, am a servant of you from of old, a heifer from your stable, a foundation stone (upon which) you (can rest). You, my lady, reared me and Hattusili, your servant, to whom you espoused me, was closely associated with the Storm God of Nerik, your beloved son… The festivals of you, the gods, which they had stopped, the old festivals, the yearly ones and the monthly ones, they shall celebrate for you, the gods. Your festivals, O gods, my lords, shall never be stopped again! For all our days will we, your servant and your handmaid, worship you. This is what I, Puduhepa, your handmaid, lay in prayer before the Sun Goddess of Arinna, my lady, the lady of Hatti lands, the queen of heaven and earth. Sun Goddess of Arinna, my lady, yield to me, hearken to me! Among men, there is a saying: ‘To a woman in travail the god yields her wish.’ Since I, Puduhepa, am a woman in travail and since I have devoted myself to your son, yield to me, Sun Goddess of Arinna, my lady! Grant to me what I ask! Grant life to Hattusili, your servant! Through the good women and the mother goddesses, long and enduring years and days shall be given to him.

GOETZE 1950b, 393-394 (KUB XXI 27)

Lawcourt Protocol

(Lawsuit opened by Queen Puduhepa against GAL.dU and his father Ukkura)

Bogazkoy (Hattusa)

Hittite Empire, mid 13th century BC.

Baked clay. h:24.8 cm. w: 18.9 cm th:5 cm

Istanbul Archaeology Museum, Bo.2131

50+45 lines on the front face in two columns, 48+51 on the back face. Restored from many fragments; missing and broken in places.

From this document, we learn that Queen Puduhepa was in charge of the administration of justice and that having discovered an impropriety, she has made an independent complaint to the court. The people accused in the queen’s lawsuit, to whom valuable goods and animals were entrusted and are now missing, have been summoned to swear at the temple of Lelvani, Goddess of the Underworld and Hell. Before the court, GAL.dU says that he has not stolen the goods, but has given them to his mother, considering himself to be innocent. This is also evidence of the importance given to mothers (i.e. women) at those times. Extracts from the court proceedings are as follows:

…The queen speaks thus: Let the salasa-workers (and) the gold-smiths go along; let GAL.dU (and) Ukkura swear without lying at the temple of the Goddess Lelvani’… Ukkura, the queen’s ‘leader of ten’, has sworn (and) under oath has made the following statement: I have never done anything wrong with the king’s stores which are always with me. I have taken nothing for myself. Moreover, I have never taken away anything that the queen has entrusted to me. The horses and mules that I had belonged to me… GAL.dU spoke thus before the god: I took for myself the ornamental pieces of three horses’ harnesses for the annual festival. And I took for myself two mules. They died whilst they were with me… From the stores entrusted to me which belonged to the seal house of the city of Partiya, I took for myself the following: 2 saddle-cloths and a kugulla-vessel, GAL.dU sent to his. I took for myself and sent to my mother 10 utensils of bronze, 1 lance, 1 bowl for washing hands, 1 copper measuring cup, 1 copper sieve, 1 large ax, 1 cart with its leather trappings… The bow with gold inlay checked by the queen. I found opened. And the(gold) inlay had been stolen. I did not take the gold myself. And I do not know who stole the (gold) inlay. But on seeing this, I was afraid, and I took gold from my mother and had it fixed in place again…

This text, which contains the testimony of several witnesses, ends abruptly because the tablet is fragmentary; and the court decision is unfortunately not known. (Not included in the exhibition.)

WERNER 1967, 1-20, (Kub XIII 35)

Letter from Egyptian King Ramses II to Hittite Queen Puduhepa

Bogazkoy (Hattusa)

Hittite Empire, 13th century BC.

Language: Akkadian

Baked clay. h: 8.5 cm.,w: 6.7cm. th: 2.6 cm.

Istanbul Archaeology Museum, BO. 1231

The piece from the upper left corner of the tablet. On the back face, there is no writing at the lower left, and the upper right face is broken. Queen Puduhepa had equal rights and authority with her husband, the Great King Hattusili III, and that, always by his side, she performed her duties independently. In particular, letters sent to her personally from the Egyptian King Ramses II are the word for the same as those he sent to her husband Hattusili III. Extracts from a letter sent from Ramses II to Queen Puduhepa, in which he addressed her as Great Queen and my sister are as follows:

The Great King, the king of Egypt, son of the Sun, Ramses beloved of Amon, speaks thus: Speak to the queen of the Hatti land, The Great Queen Puduhepa: See then, I, your brother, am well. My houses, my sons, my armies, my horses, my chariots and the things in my lands, are very well (in comfort). May you, my sister,(also) be well! May your houses, your sons, your armies, your horses, your chariots, your nobles, and the things in your lands be very very well! Speak thus to my sister: Look now! My messengers have come to me together with my sister’s messengers and have brought me the news that my brother, the king of the Hatti land, the Great King, is in good health… Speak thus to my sister: The great King, the king of the Hatti land, has written to me thus: ‘Let the people come to pour sweet-smelling oil on my daughter’s head and let them take her to the house of the Great King, the king of Egypt, my brother. ‘Look now! My brother wrote this to me. This decision written to me by brother is wonderful. The Sun God has approved of him. The Weather God has approved of him. And the Egyptian gods and the Hatti gods have approved of him for making this fine decision in order to join two great lands into one forever…

EDEL 1953.262-273 (KUB lll. 63).

Letter from Egyptian King Ramses II to Hittite Queen Puduhepa

Bogazkoy (Hattusa)

Hittite Empire, 13th century B.C.

Language: Akkadian

Baked clay. h: 17.5 cm. w:10.9 cm. th: 3.8 cm.

Ankara Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, 14265

45 lines on the front face of the tablet, 34 on back. Cracked in places, with pieces missing. This tablet, together with A 139 and other correspondence found at Bogazkoy between Ramses II and either Hattusili III or Queen Puduhepa, give information about the plans to send their daughter Hittite princess as a wife for Ramses II and a queen for Egypt. Despite all these texts and the information from Egyptian sources, however, it is not known for certain that such a princess did in fact reign in the Egyptian palace. The princess was to be sent with gifts and accompanied by couriers and was to be met by Egyptian representatives who would accompany her to Egypt. The text opens as follows:

The king of Egypt, the Great King, the son of the Sun, beloved of the God Amon, the First Great king, the king of the land of Egypt, will speak thus to the Great Queen Puduhepa of the Hatti land, my sister: Look! Ramses, beloved of the God Amon, the Great King of the land of Egypt, as well. His houses, his sons, his armies, his horses, his chariots and the things in his country are (also) very well. May you, Great Queen of the Hatti land, my sister, also be well!! May your houses, sons, horses, chariots and the things in your country (also) be well!! Here, Ramses II addressing Queen Puduhepa as ‘Great Queen’ and ‘my sister’, says that her decision to give her daughter is also approved by the gods, and he entreats the gods thus:…” And you (gods) give her to the house of the king! And she will be the ruling (queen) of the Egyptians…

(KBo XXVIII 23)

Letter from Egyptian King Ramses II to Hittite Queen Puduhepa

Bogazkoy (Hattusa)

Hittite Empire, 13th century B.C.

Language: Akkadian

Baked clay. h:15.2 cm. w:9.7cm. th: 3.5 cm

Ankara. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, 136-1-88

27 lines on the front face, 4 on back. Tablet dark grey in color, restored from two pieces. Although Queen Puduhepa, the wife of the Hittite King Hattusili III, played a very important role in diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian and Hittite states, only a single letter is known written by Queen Naptera, wife of Ramses II. The contents of this letter are as follows:

The great Queen Naptera of the land of Egypt speaks thus: Speak to my sister Puduhepa, the Great Queen of the Hatti land. I, your sister, (also) be well!! May your country be well. Now, I have learned that you, my sister, have written to me asking after my health. You have written to me asking after my health. You have written to me because of the good friendship and brotherly relationship between your brother, the king of Egypt, The Great and the Storm God will bring about peace, and he will make the brotherly relationship between the Egyptian king, the Great King, and his brother, the Hatti King, the Great King, last forever… See, I have sent you a gift, in order to greet you, my sister… for your neck (a necklace) of pure gold, composed of 12 bands and weighing 88 shekels (8*88=704 gr.), colored linen maklalu-material, for one royal dress for the king… A total of 12 linen garments.