TILES & CERAMIC ART IN TURKEY

Tiles and ceramics make up another group of handicrafts in Turkey that flourished in Turkish hands in Anatolia and achieved previously unattainable levels of perfection.

Seljuk tiles produced from the end of the 12th century and throughout the whole of the 13th represent one of the most successful forms of architectural decoration to emerge during the Middle Ages.

The Seljuks developed a wide repertoire of applications ranging from glazed brick to mosaic and from colored-glaze square tiles to the star-shaped luster tiles decorated with mythological creatures in Kubadabad Palace.

Examples of the wealth of Seljuk architectural tiles are to be found all over the world and there are two excellent collections in the Karatay Medrese Museum in Konya.

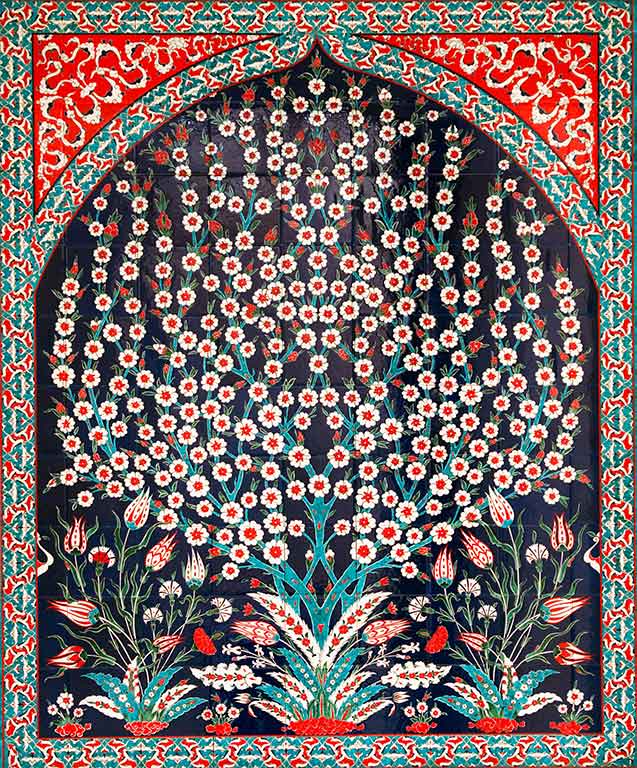

Among the Ottomans, the 16th century marks the high-water-mark of tile, ceramic, and colored-glass manufacturing. Iznik tiles and pottery from this period achieved new heights in the technique of underglaze decoration.

Outstanding examples made during this century still gladden the heart adorning the monuments of the architect Sinan while the collections of Topkapi Palace and the Tiled Kiosk are instructive and illuminating.

Concentrated in the two principal centers of Iznik and Kutahya, Ottoman tile and ceramic-making went into a decline in the 17th century.

An attempt to revive the industry at Tekfur Sarayi in Istanbul in the 18th century was only temporarily successful. You can find these remarkable tiles and ceramics reproductions in Istanbul, in Cappadocia, and on the Turkish Coasts.

History of the Tiles & Ceramics Art

There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures, like that of the Nok in Africa over 2,000 years ago. Cultures especially noted for ceramics include the Chinese, Cretan, Greek, Persian, Mayan, Japanese, and Korean cultures, as well as the modern Western cultures.

The earliest evidence of glazed brick is the discovery of glazed bricks in the Elamite Temple at Chogha Zanbil, dated to the 13th century BC. Glazed and colored bricks were used to make low reliefs in Ancient Mesopotamia, most famously the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (ca. 575 BC), now partly reconstructed in Berlin. Mesopotamian craftsmen were imported for the palaces of the Persian Empire such as Persepolis. The tradition continued, and after the Islamic conquest of Persia colored and often painted glazed bricks or tiles became an important element in Persian architecture, and from there spread to much of the Islamic world, notably the Iznik pottery of Turkey under the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries.

During the 16th century, the decoration of the pottery gradually changed in style, becoming looser and more flowing. Additional colors were introduced. Initially, turquoise was combined with the dark shade of cobalt blue and then the pastel shades of sage green and pale purple were added. Finally, in the middle of the century, a very characteristic bold red replaced the purple and a bright emerald green replaced the sage green. From the last quarter of the century there was a marked deterioration in quality and although production continued during the 17th century the designs were poor, as the city’s role as primary ceramics producer was taken up by Kutahya.