For thousands of years, Turkic people spread far and wide across Eurasia, but Mongolia is of particular importance in the study of Turkish history on account of the numerous ancient monuments which provide valuable evidence for archaeologists, linguists, and anthropologists. The inscriptions on these monuments are the earliest documents in the Turkish language and throw light on both the history and culture of their time. The monuments are concentrated in the Orhun, Tola, Ongin, and Selenge river basins.

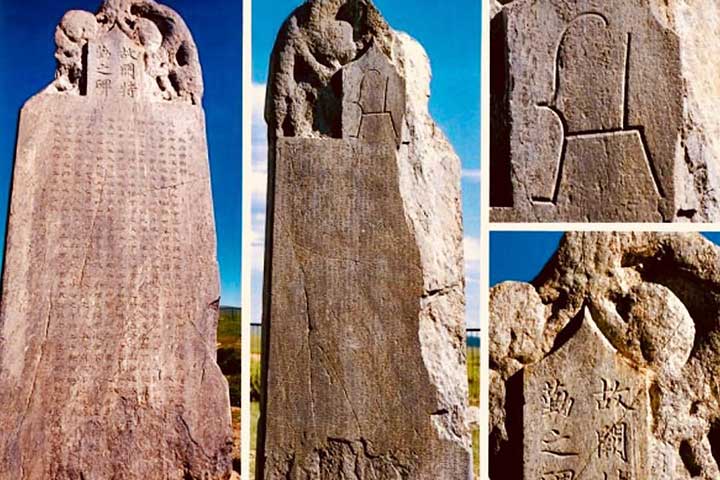

The most important of all are the monuments of Kul Tigin, Bilge Kagan and Tonyukuk. The two former are the oldest of all and are generally referred to as the Orkhon Inscriptions since they are situated close to the former bed of the River Orhun in Mongolia.

The Tonyukuk Inscription lies further eastwards, at Bayn Tsokto between the city of Nalaih and the River Tola, about 50 kilometers southwest of the Mongolian capital of Ulan Bator (Ulaanbaatar).

The first person to bring these monuments to the attention of western scholarship was a Swede, Philipp Johann Von Strahlenberg, who published his findings in 1730.

His account of these Turkish inscriptions turned the eyes of many researchers to the Asian steppes. In 1889 Nikolay Mihaylovich Yadrintsev discovered two further and imposing monuments bearing inscriptions around Khoso Tsaydam near the River Orhun in northern Mongolia. These, it later emerged, were the monuments of Kul Tigin and Bilge Khagan. The inscriptions were deciphered in 1893 by Wilhelm Thomsen, Professor of Philology at Copenhagen University. While Thomsen was busy transcribing the inscriptions, the Russian scholar Radloff was studying the Kul Tigin and Bilge Khagan monuments. The Bilge Khagan Inscription was erected in 735 by Bilge Khagan’s youngest son Tengri Khagan. The inscription, which is broken in four parts today, is a relation of events as if told by Bilge Khagan.

The Kul Tigin Inscription is in a better state of preservation and is still standing. It was erected in 732 in commemoration of Bilge Khagan’s younger brother Kul Tigin. The two inscriptions stand one kilometer apart. A fence has been erected around the monuments and the remains of their complexes for protection.

The Tokyukuk Inscription, which consists of two stones with inscriptions on all four faces, is thought to date from 720-725. The narrator of this inscription is Bilge Tonyukuk.

The script used on the Orkhon (Orhun) Inscriptions is the oldest alphabet used to write any Turkic language and is generally described by Turkologists as ancient Turkish runic script. The term runic derives from similarities between these letters and those of ancient Scandinavian inscriptions known as runes. Like all writing systems of Semitic origin, ancient Turkish runic script was written from right to left. The letters are designed for carving on stone and other hard materials.

The inscriptions describe the military history of the Gokturk Khanate as if told by the Gokturk ruler Bilge Khagan and his minister Tokyukuk. Each inscription begins with one sentence about the creation of the world and human beings; and after a brief outline of the First Eastern Turkish Khanate, it continues with a detailed account of the political and military history of the Second Khanate up to the death of its founder Kul Tigin in 731. The Tokyukuk Inscription concentrates mainly on the achievements of Ilteris Khagan and Bilge Khagan’s uncle Kapgan Khagan, and the services rendered by Tonyukuk himself.

Under the Turkish Monuments in Mongolia Project launched in 1995 a joint team of Turkish and Mongolian scientists has been conducting epigraphic, topographic and photogrammetric studies of the monuments, and archaeological excavations at the sites.

The information they have gathered throws important new light on Turkish culture and civilization. This year, work has centered on the Orhun Valley where the Bilge Khagan and Kul Tigin inscriptions are situated. This is an area of great archaeological interest, and research will continue for many years yet. It is planned to eventually restore the complexes in which the monuments stand, and to conduct similar studies on the site of the Tonyukuk Inscription and other Turkish monuments in Mongolia. Once restored, the complexes are expected to be a major tourist attraction.

This ambitious project being organized by the Turkish Agency for Cooperation and Development (TIKA) at a distance of 10,000 kilometers away from Turkey is as prestigious as it is important to our knowledge of early Turkish history.

Up until now, the Gokturk monuments have been a subject only of linguistic and epigraphic study, but now this comprehensive project is also investigating these monuments and tomb complexes from the point of view of art history and archaeology.

Progress is being followed with interest by UNESCO and scholars from many countries. There can be no doubt that this work will open new horizons for future generations of scholars working in this area.